Age of Onset of Mental Disorders a Review of Recent Literature

Abstract

Promotion of good mental wellness, prevention, and early intervention before/at the onset of mental disorders improve outcomes. However, the range and peak ages at onset for mental disorders are not fully established. To provide robust, global epidemiological estimates of age at onset for mental disorders, nosotros conducted a PRISMA/MOOSE-compliant systematic review with meta-assay of nascency accomplice/cantankerous-exclusive/cohort studies, representative of the full general population, reporting age at onset for any ICD/DSM-mental disorders, identified in PubMed/Web of Science (upwardly to sixteen/05/2020) (PROSPERO:CRD42019143015). Co-primary outcomes were the proportion of individuals with onset of mental disorders before age 14, 18, 25, and superlative age at onset, for whatsoever mental disorder and beyond International Nomenclature of Diseases 11 diagnostic blocks. Median age at onset of specific disorders was additionally investigated. Across 192 studies (due north = 708,561) included, the proportion of individuals with onset of any mental disorders before the ages of fourteen, eighteen, 25 were 34.half dozen%, 48.4%, 62.5%, and peak age was fourteen.five years (chiliad = 14, median = xviii, interquartile range (IQR) = 11–34). For diagnostic blocks, the proportion of individuals with onset of disorder earlier the age of fourteen, 18, 25 and peak age were as follows: neurodevelopmental disorders: 61.5%, 83.ii%, 95.8%, v.5 years (k = 21, median=12, IQR = 7–16), anxiety/fear-related disorders: 38.i%, 51.eight%, 73.3%, v.5 years (chiliad = 73, median = 17, IQR = 9–25), obsessive-compulsive/related disorders: 24.6%, 45.1%, 64.0%, 14.5 years (k = 20, median = 19, IQR = 14–29), feeding/eating disorders/problems: 15.eight%, 48.1%, 82.4%, xv.5 years (m = 11, median = 18, IQR = 15–23), weather condition specifically associated with stress disorders: 16.9%, 27.6%, 43.1%, fifteen.5 years (k = 16, median = 30, IQR = 17–48), substance use disorders/addictive behaviours: two.9%, 15.2%, 48.eight%, 19.5 years (k = 58, median = 25, IQR = 20–41), schizophrenia-spectrum disorders/primary psychotic states: three%, 12.3%, 47.eight%, 20.5 years (k = 36, median = 25, IQR = xx–34), personality disorders/related traits: i.9%, 9.6%, 47.seven%, 20.5 years (k = 6, median = 25, IQR = 20–33), and mood disorders: 2.five%, 11.five%, 34.5%, 20.5 years (k = 79, median = 31, IQR = 21–46). No pregnant divergence emerged by sex, or definition of age of onset. Median historic period at onset for specific mental disorders mapped on a time continuum, from phobias/separation anxiety/autism spectrum disorder/attention arrears hyperactivity disorder/social feet (8-13 years) to anorexia nervosa/bulimia nervosa/obsessive-compulsive/binge eating/cannabis use disorders (17-22 years), followed by schizophrenia, personality, panic and alcohol use disorders (25-27 years), and finally post-traumatic/depressive/generalized anxiety/bipolar/astute and transient psychotic disorders (30-35 years), with overlap among groups and no significant clustering. These results inform the timing of good mental wellness promotion/preventive/early intervention, updating the current mental health system structured around a child/developed service schism at age eighteen.

Introduction

Individuals with mental disorders accept a decreased life expectancy of 10–15 years in comparison with the general population [i,two,three,4]. Early interventions at the starting time onset of mental disorders tin can ameliorate several outcomes [v, vi]. Principal indicated prevention in those at clinical high take chances has the potential to alter the form of the disorder and amend outcomes [seven,viii,9]. For example, young people with attenuated symptoms for psychosis [10,xi,12,13] and functional impairments accumulate several run a risk factors and take a 25% probability of developing the disorder over 3 years [14]. Clinical care for these individuals is typically implemented in specialised clinical services [xv,16,17,18] and has the potential to delay or impede the transition to psychosis, although the efficacy of preventive interventions awaits more than robust prove [nineteen,20,21]. Targeted preventive approaches involve screening programmes in asymptomatic individuals who have significant chance factors for certain psychiatric disorders [7, 22, 23] (chief selective prevention [7, 8]) or public wellness campaigns in the general population (primary universal prevention) [7, 8, 24]. To engagement, these initiatives accept been mostly piloted for young people with emerging severe mental disorders [8]. A further complementary approach is to promote good mental health, equally opposed to preventing mental disorders [7, 25, 26].

Although promotion of good mental health, prevention and early intervention can be implemented over the lifespan, the benefits are maximal when immature people are targeted at around the time of onset of mental disorders. Unfortunately, the elevation ages and ranges at onset for mental disorders are not fully established, with conflicting findings across [27, 28] and within studies [29], partly due to methodological limitations, including selection biases in recruitment for clinical studies [30]. General population-level studies (birth cohort, cross-sectional or incidence studies) provide the about robust onset age estimates [30]. However, to date, no comprehensive epidemiologically sound, large-calibration meta-analysis has pooled information from these population-based studies that are representative of the general population to approximate the height age at the onset beyond the globe and the proportion of individuals with mental disorders at specific age points. This study'south goal was to make full this gap aiming to optimise timely intervention, prevention and promotion of skilful mental health opportunities at the time of onset of mental disorders.

Method

Search strategy

A study protocol was registered and is publicly available on PROSPERO (CRD42019143015). We performed a systematic review adhering to the preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses (PRISMA) recommendations [31] (e-Table one) and the meta-analysis of observational studies in epidemiology (MOOSE) guidelines (e-Table 2) [32].

At least two authors (MO, ER, LS, MS, all MDs) independently searched PubMed and Web of Science using the post-obit terms: "age at onset" (topic) and "mental disorder" (topic), plus "birth accomplice" (topic) and "mental disorder" (topic), plus "incidence" (topic) and "mental disorder" (topic), without restriction to the type of mental disorder. Additionally, reviews and reference lists of included studies were manually searched. The literature was searched from database inception until 16/05/2020. Hits were outset screened at the title/abstract level, then full texts of the remaining articles were assessed, recording reasons for exclusion (as per the criteria noted below).

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Included were: (i) original nascence accomplice or cross-sectional studies retrospectively assessing age at disorder onset, or prospective incidence studies [30], (ii) focusing on the general population, (iii) assessing historic period at onset of mental disorders, defined according to international classification diseases (ICD) or diagnostic and statistical manual (DSM)-any version criteria, or past established psychometric instruments with validated cutting-offs that defined ICD/DSM diagnostic categories, (iv) written in English language.

Excluded were: (i) studies sampling clinical groups that were non representative of the general population, (ii) studies assessing the prevalence, not onset age of mental disorders, (iii) reviews, meta-analyses, instance reports or other not-original studies, (iv) non-English language articles.

Data extraction

The following variables were extracted into pre-defined excel spreadsheets: DOI/PMID, author, publication year, country of study, study pattern (birth cohort, cross-sectional, incidence studies, all representative of the general population), proper name of the cohort (if available), ICD/DSM diagnostic criteria, onset definition (start symptoms, commencement diagnosis, first hospitalisation), a specific type of mental disorder, sample age range, number of participants, number of cases developing incident mental disorders. Historic period at onset of mental disorders was extracted as available in each of the included studies (run into statistics). Data extraction was performed independently past the same pairs of authors who performed the literature screening.

Study quality assessment

To the best of our cognition, no quality assessment measure has been validated for the blazon of studies included in the current meta-analysis. Therefore, the risk of bias was evaluated with an advertizing-hoc list of criteria derived from the Newcastle-Ottawa scale (NOS) [33], which included the definition of onset historic period of the mental disorder, diagnostic criteria employed, and study design. However, since these criteria were not validated, they were not employed to categorise studies co-ordinate to their quality; they were just used for descriptive reporting.

Statistical analysis

Study-defined age at onset of mental disorders encompassed: (i) mean and standard deviation (SD), percentiles, median and/or interquartile range (IQR) of age at disorder onset; (ii) proportion of cases of a sample whose historic period at disorder onset fell into a certain age group, (iii) number of incident cases developing mental disorders, separately for historic period groups (due east.g., for national registries).

Nosotros defined co-chief outcomes every bit the proportion of individuals with historic period at disorder onset of any and specific mental disorder groups before 14, 18 and 25 years old, and peak age at onset for any mental disorder and for each diagnostic group. Diagnostic groups matched all nineteen ICD-eleven diagnostic blocks nether "Mental, behavioural or neurodevelopmental disorder", namely neurodevelopmental disorders, schizophrenia-spectrum and primary psychotic disorders, catatonia, mood disorders, anxiety and fear-related disorders, obsessive-compulsive or related disorders, disorders specifically associated with stress, dissociative disorders, feeding or eating disorders, elimination disorders, disorders of bodily feel, disorders due to substance use or addictive behaviour, impulse-command disorders, confusing behaviour or dissocial disorders, personality disorders and related traits, paraphilic disorders, factitious disorders, neurocognitive disorders, disorders associated with pregnancy childbirth or puerperium. Individual studies adopted different age subgroupings and age ranges. To our knowledge, there is no standard method to pool such varying descriptive statistics of the distribution of a variable (age at onset of mental disorders) when the variable of interest follows a not-normal distribution and/or is heterogeneously censored. Therefore, we take developed an ad-hoc method to meta-analyse these estimates. To assess these co-primary outcomes, we first estimated the histogram of the historic period at disorder onset that minimised the sum of squared errors (SSE) of the written report-reported information. From this histogram, we and so derived peak age at onset, also as the proportion of individuals showing an onset earlier 14, 18 and 25 years of age, and the 25%, 50% and 75% percentiles of the age at disorder onset. Thereafter, we used an empirical bootstrap approach [34] to estimate the 95% confidence intervals of age at onset.

Additional sensitivity analyses were performed. Start, nosotros repeated the analyses for specific mental disorders, pre-selected on the basis of their epidemiological and clinical relevance: attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), autism spectrum disorder (ASD), generalised feet disorder (GAD), panic disorder, separation feet disorder, specific phobia, social anxiety disorder, obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), disorders due to use of alcohol, disorders due to use of cannabis, anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, binge eating disorder, depressive disorders, bipolar or related disorders (bipolar disorder), astute and transient psychotic disorders (ATPD), schizophrenia, and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). 2d, we repeated analyses for any disorder, stratifying past onset definition (i.e., get-go symptoms, first diagnosis, first hospitalisation). Tertiary, we repeated the analyses for any disorder stratifying by sexual practice. Finally, we compared the median age at onset between each pair of specific mental disorders, counting the proportion of bootstrapped randomisations in which the median age at onset of 1 disorder was larger than the median age of the other disorder (alpha = 0.05, two-sided).

For all analyses, we required ≥2 studies to gauge the histogram and to apply the bootstrap process. For full details regarding the statistical analysis, see east-methods.

Results

Literature search and database

Nosotros identified 5,442 possible publications afterwards removing duplicates, of which 4,516 were excluded after title/abstract screening. An additional 734 publications were excluded later on full-text review (run into e-Fig. one and supplementary textile—e-Table iii—for full details). For characteristics of the 192 included studies (nativity cohort studies = 15, cross-sectional studies = 150, incidence studies = 27), run into due east-Table 4. These studies were comprised of data from 708,561 individuals, all of whom were diagnosed with a mental disorder. Overall, 54 studies were set up in U.S., 23 studies in multiple countries, 11 in Australia, 10 in Finland, 8 in Germany, half-dozen each in Canada and kingdom of the netherlands, 5 in Cathay, Denmark, South Africa, Spain, United kingdom, four in State of israel, S Korea, Sweden, three in Ethiopia, Mexico, New Zealand, Nigeria, Switzerland, Taiwan, two in French republic, Iraq, Singapore, and 1 study each in additional countries.

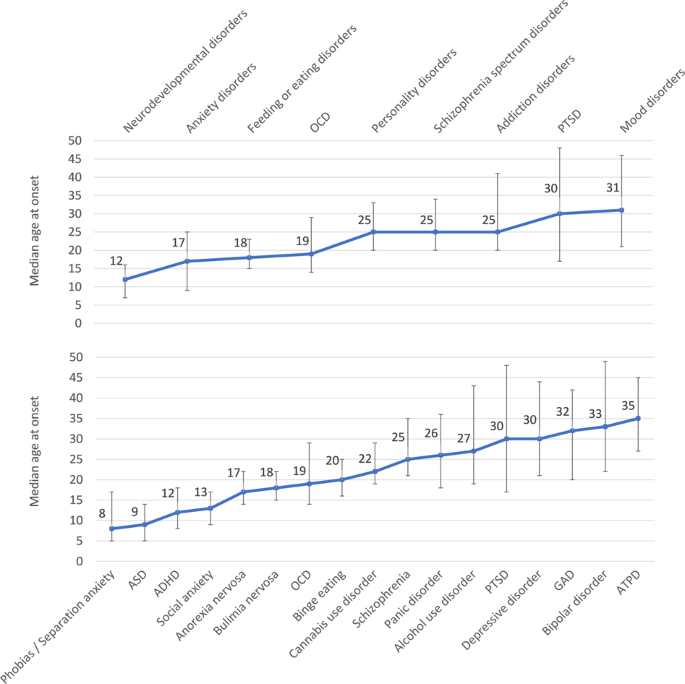

The line indicates the median age at onset of mental disorders (ICD-eleven diagnostic blocks or spectra to a higher place, specific mental disorders below), the bar indicates the 25th and 75th percentiles. ICD-11 blocks of mental disorders. Addiction disorders: disorders due to substance use or addictive behaviour, Anxiety and fear: anxiety and fear-related disorders, OCD related: obsessive-compulsive or related disorders, Schizophrenia spectrum disorders: schizophrenia-spectrum and primary psychotic disorders. ICD-11 specific mental disorders. ADHD attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, ASD: autism spectrum disorder, ATPD, acute and transient psychotic disorder; Binge eating: binge eating disorder, Bipolar disorder: bipolar or related disorders, GAD generalised feet disorder, OCD obsessive-compulsive disorder, Phobia: specific phobia, PTSD post-traumatic stress disorder, Separation feet: separation feet disorder, Social anxiety: social anxiety disorder.

There were insufficient studies for inclusion on catatonia, dissociative disorders, elimination disorders, disorders of actual experience, impulse-command disorders, disruptive behaviour or dissocial disorders, paraphilic disorders, factitious disorders, neurocognitive disorders, and disorders associated with pregnancy childbirth/puerperium.

Global age at the onset across diagnostic spectra of mental disorders

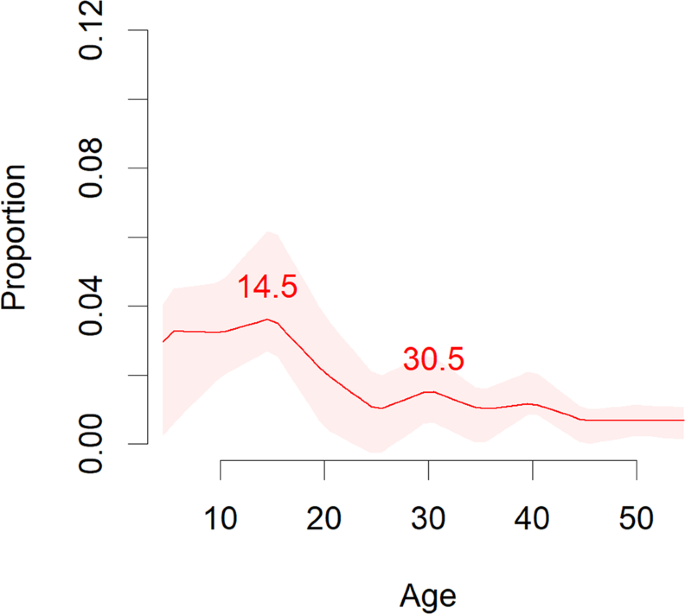

The proportion of individuals with age at onset earlier fourteen, 18 and 25 years of historic period and meridian historic period at onset for diagnostic spectra (co-principal outcome measures) are reported in Table one. Overall, before historic period 14, xviii, and 25 years, a disorder had already emerged in 34.6%, 48.4%, and 62.5% of individuals (Table 1).

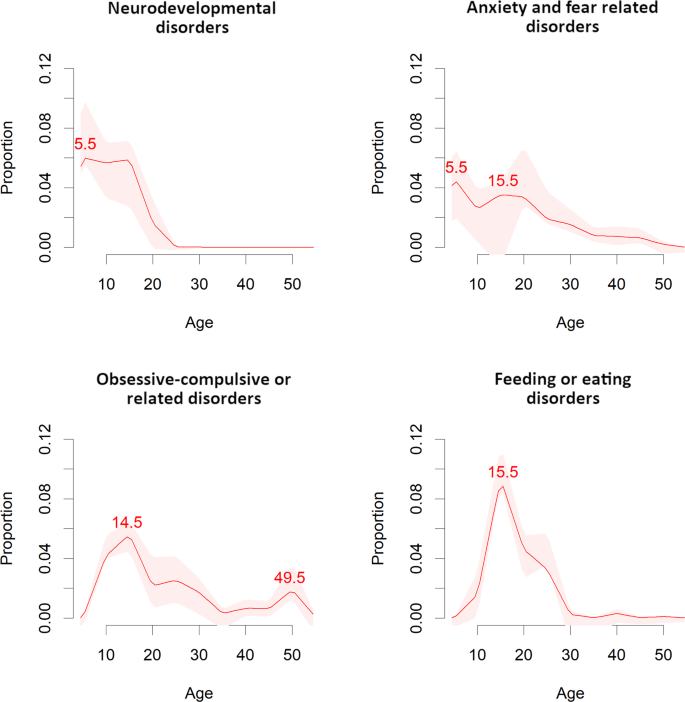

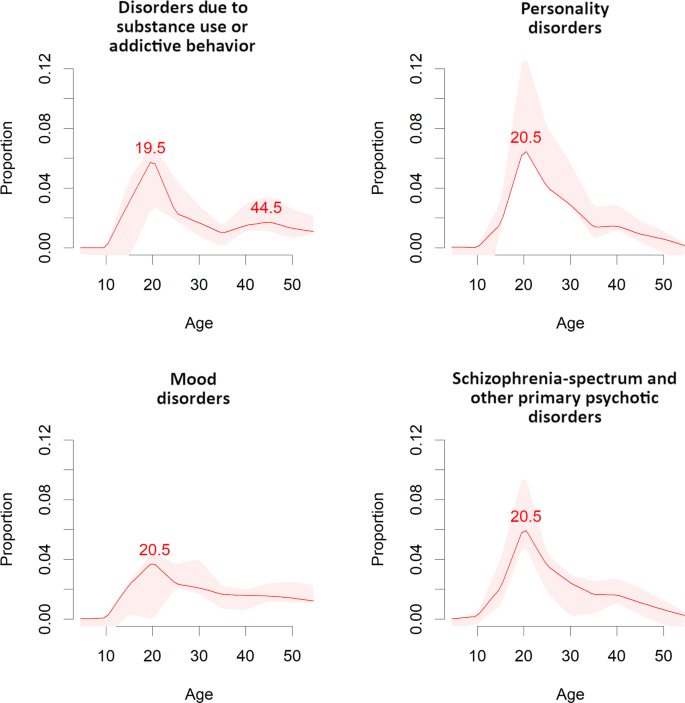

Corresponding figures were, respectively, for neurodevelopmental disorders: 61.5%, 83.ii%, 95.viii%, for anxiety/fearfulness-related disorders: 38.1%, 51.eight%, 73.3%, for obsessive-compulsive/related disorders: 24.six%, 45.i%, 64.0%, for feeding/eating disorders: 15.viii%, 48.1%, 82.4%, for disorders specifically associated with stress: 16.9%, 27.6%, 43.i%, for substance utilise/addictive behaviour disorders: 2.nine%, xv.two%, 48.eight%, and for schizophrenia-spectrum/primary psychotic disorders: three%, 12.3%, 47.8%, for personality disorders/traits: 1.ix%, 9.six%, 47.seven%, and for mood disorders: two.5%, xi.5%, 34.5%.

Curves representing the median, 25th, and 75th percentiles and peak age at onset for mental disorder spectra are reported in Figs. 1–4. The height and median age at onset for whatsoever mental disorder were 14.5 years and 18 years. The primeval age peaks of disorder onset were: neurodevelopmental disorders (peak = five.5/median = 12 years), anxiety/fear-related disorders (elevation = 5.5/median = 17 years), obsessive-compulsive/related disorders (peak = fourteen.5/median = 18 years), feeding/eating disorders (height = fifteen.5/median = eighteen years), disorders specifically associated with stress (elevation = fifteen.5/median = xxx years), substance use/addictive behaviour disorders (acme = 19.5/median = 25 years), schizophrenia-spectrum/primary psychotic and personality disorders/traits (peak = 20.five/median = 25 years), and mood disorders (elevation = xx.5/median = 31 years). Second historic period peaks emerged for any mental disorder at (peak = thirty.five years), feet/fear-related disorders (peak = 15.5 years), obsessive-compulsive/related disorders (tiptop = 49.5 years), disorders specifically associated with stress (peaks = 30.5 and 49.five years), and substance apply/addictive behaviour disorders (peak = 44.5 years).

Meta-analytic epidemiological proportion (y-axis) and peak age at onset (red line) for any mental disorders in the general population, with 95%CIs (pink shadows).

Meta-analytic epidemiological proportion (y-axis) and peak age at onset (carmine line) for neurodevelopmental, anxiety and fear-related, obsessive-compulsive related, and feeding or eating disorders (ICD-eleven blocks) in the general population, with 95%CIs (pink shadows).

Meta-analytic epidemiological proportion (y-centrality) and peak age at onset (crimson line) for disorders due to substance use or addictive behaviour, personality, mood, and schizophrenia-spectrum and primary psychotic disorders (ICD-11 blocks) in the full general population, with 95%CIs (pink shadows).

Sensitivity analyses

The proportion of individuals with historic period at the onset before xiv, 18 and 25 years of age for specific mental disorders are reported in Table ane. Overall, the proportion of patients developing disorders before age 25 is more 9 out of ten for ASD and ADHD; nine out of ten for social feet disorder; around eight out of 10 for specific phobia/separation feet disorders and anorexia nervosa; 7 to eight out of ten for binge eating disorders; six to seven out of ten for OCD and disorders due to use of cannabis; four to five out of ten for disorders due to apply of alcohol, schizophrenia, PTSD, panic disorder, and personality disorders; three to iv out of ten for GAD, bipolar/related disorders, and depressive disorders; and ii out of ten for ATPD. The curves representing the meridian age at onset for specific mental disorders are presented in eastward-Figs. 2–17.

Every bit reported in Tabular array 2, the age at onset was mostly similar between males and females, although there was a trend towards younger ages for males in disorders due to substance use or addictive behaviours (median = 4 years earlier), mood disorders (median = ii years earlier) or schizophrenia-spectrum and main psychotic disorders (median = ane twelvemonth earlier). Similarly, there were little differences in historic period at onset amidst studies where onset was defined according to showtime symptoms, starting time diagnosis or showtime hospitalisation, although in that location was a tendency towards younger ages for kickoff symptoms than for the commencement diagnosis in disorders due to substance use/addictive behaviours (median symptoms 9 years earlier), mood disorders (median 8 years earlier), anxiety and fear-related disorders (median three years earlier). For schizophrenia-spectrum and primary psychotic disorders, we observed a tendency from symptoms to hospital access (median a year later) to diagnosis (median another year afterwards). There were other pocket-sized differences in disorders with fewer (<10) separate studies for sex activity or onset definition, for which we suggest caution every bit the estimations may be less accurate than others.

Despite some differences shown in e-Table 5, the median age at onset of specific mental disorders maps on a continuum, with no clear clustering across different disorders. Descriptively, the primeval median age of onset was observed for phobias/separation anxiety, ASD, ADHD, social anxiety disorders (8-xiii years), followed by anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, OCD, binge eating, cannabis use disorders (17-22 years), subsequently schizophrenia, personality and alcohol use disorders (25-27 years), and, finally, PTSD, depressive disorder, GAD, bipolar disorder, and ATPD (30-35 years).

Discussion

This is the outset big-scale epidemiological meta-analysis that includes all available general population birth, cantankerous-sectional and incidence studies investigating the historic period at onset of any ICD/DSM-mental disorders. Overall, the global onset of the first mental disorder occurs before age 14 in one-3rd of individuals, historic period xviii in almost half (48.4%), and before age 25 in half (62.five%), with a superlative/median age at onset of 14.five/eighteen years beyond all mental disorders. However, there was significant variability in global age at onset and peak age beyond mental disorders. These findings can inform the timing and resource allocation regarding early intervention and preventive approaches.

To our best knowledge, this study is the first fully epidemiological and largest [35,36,37,38] meta-analysis on historic period at onset of mental disorders globally. It likewise represents the most comprehensive approach, encompassing all ICD-11 diagnostic spectra for which nosotros found eligible studies, allowing comparative transdiagnostic analyses across unlike categories of mental disorders [39, 40]. Furthermore, per protocol, loftier-quality population-level studies were included that are less likely to be affected by biases, meeting previous methodological recommendations [30]. Moreover, information from all continents of the globe were available, providing global estimates on the age at onset of mental disorders. Importantly, the statistical arroyo of this meta-analysis provides an approximate of age at disorder onset distribution throughout the lifespan, going beyond mere centrality estimates.

The meta-epidemiologic results of this work show that mental disorders have onset when dramatic biological changes in the brain occur, from childhood, through adolescence, to adulthood, that involves grayness-matter density, cerebral metabolic charge per unit, synaptic density, white affair growth and myelination [41]. The in-depth, robust epidemiological evidence provided here has several clinical implications. Firstly, the onset of the offset mental disorder before age xiv, xviii and 25 in ane 3rd, half and 62.5% and meridian/median historic period of xv.5/18 years demonstrate that adult mental disorders originate early during the neurodevelopmental phases of life and peak, in pooled mental disorders, by mid to late boyhood [42,43,44]. Given that mental disorders are 1 of the five well-nigh common ailments leading to morbidity, mortality and dysfunction among young people worldwide [45], the electric current findings are relevant to policymakers and healthcare providers. These results suggest that the next generation of mental wellness research should prioritise designing and funding global early interventions [v, 46] and indicated, selective and/or universal preventive interventions for mental disorders during mid/tardily adolescence and immature machismo that are currently lacking [viii].

Secondly, this study provides disorder-specific estimates of historic period at disorder onset that impacts mental health service configuration and commitment. For nigh half of mental disorders (Tabular array 2), disorder onset occurs well before age eighteen. Disorder median age at onset occurred during the neurodevelopment, within historic period xiv for the vast majority of phobias and separation anxiety, ASD, ADHD, and for more than so one-half in social anxiety disorders. For these disorders, good mental health promotion, along with preventive and early intervention approaches need to target these neurodevelopmental periods, mainly during pre-schoolhouse and primary schoolhouse periods. Many of the risk and protective factors that touch on the neurodevelopment of individuals with these disorders are known [23, 47,48,49,50,51,52], and some of them may even impact the pre or perinatal phases [53]. A recent meta-umbrella review (i.e., a synthesis of systematic reviews of meta-analyses) has summarised take chances and protective factors (across genetics) in a comprehensive atlas [54]. Chiefly, targeting the neurodevelopmental phase has the potential to accommodate multi-endpoint numerators across mental disorders that are essential to better justify the denominator of efforts and costs for preventive and early intervention [8]. Higher median age at disorder onset during the transitional menstruum across adolescence and immature adulthood emerged for another larger grouping of mental disorders, i.e., anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, OCD, binge eating, and cannabis use disorders. For these disorders, good mental health promotion, prevention and early intervention could be delivered in primary and secondary schools [55,56,57]. A third group with median age at onset in the early adulthood included, schizophrenia, personality, panic and alcohol use disorders, and a fourth group included the remaining disorders that have a median age at onset in the afterwards adulthood, such as PTSD, GAD, depressive and bipolar disorders, and ATPD. Secondary schools and colleges could become the most important setting for mental wellness promotion, prevention and early on intervention beyond these ii groups of mental disorders. Importantly, the diagnosis of personality disorder is artifactually delayed past diagnostic criteria allowing diagnosis later historic period 18, and clinically relevant symptoms occur earlier.

For all disorders culturally and ethically- sensitive [8] promotion of expert mental health (indicated, selective and/or universal) prevention and early intervention should ideally be delivered in an integrated way that encompasses schools/colleges, and paediatricians/general practitioners, emergency departments, mental health settings, as well equally the general community [threescore]. Overall, this written report shows that any lower age threshold limiting access to mental health promotion campaigns or preventive or early interventions mental health programmes is not supported past meta-epidemiological evidence. Conversely, lower age thresholds that divide the education and training of mental health specialists or clinical services deprive individuals with developmental disorders (or other disorders with early onset) of continuity of intendance. Divisions fragment pathways to care and continued treatment from childhood through adolescence into machismo (see below) [58]. Our recommendation for mental wellness services of the future would permit soft entry points, prepare no lower historic period threshold, and loosen lower historic period intake criteria [59]. For example, an indicated prevention and early intervention model of care for mood disorders, and schizophrenia-spectrum/main psychotic disorders should ideally integrate low-threshold entry points for individuals of age younger than 18, supplemented by systematic promotion of good mental health, proactive screening for run a risk of developing specific mental disorders co-ordinate to meridian and median age at onset identified higher up, and deliver needs-based care [19, threescore, 61].

Thirdly, a farther, broader clinical implication of these results is that it demonstrates that historic period 18 as an intake threshold for adult mental wellness services is artificial and not based on global epidemiological evidence (nor on biological evidence of age when major brain changes occur [41]). To the best of our knowledge, mental wellness specialist training and mental wellness services in most parts of the globe, including North America, Australia, virtually European countries, including Italy, Germany, Uk, are divided between kid/adolescent psychiatry and adult psychiatry. Given that the vast majority of mental disorders diagnoses seen in adulthood show a superlative of onset before age 18, such a bifurcated mental health system is not prove-based and may disadvantage individuals with developmental disorders from accessing and receiving adequate and continuous care [62]. Moreover, most psychiatry training programmes fail to target the transition menses from childhood and adolescence to developed psychiatry [63]. Although many mental wellness services have tried to address this aperture of care [63, 64], meaning gaps remain. Future mental health reforms could leverage and refine clinical loftier-gamble services for young people at risk of psychosis, which typically accepts referrals aged xiv–35 years and therefore provide essential transitional intendance to this vulnerable young population [xv, 17, 58].

This written report has several limitations. First, data were besides thin to calculate country-specific estimates. However, the database included many countries worldwide, and, therefore, the estimates provided are largely representative of the global general population. Second, the 95% confidence interval for some estimates were wide since analyses for some disorders were based on few studies. Third, data were heterogeneous, making traditional meta-analytic techniques unfeasible. We, therefore, practical advanced meta-analytic techniques, including bootstrap methods that helped to accost this shortcoming and provide unified outcomes across all mental disorders. Fourth, our quality assessment was not-standardised because appropriate validated measures were not available. Notwithstanding, we per-protocol included the highest-quality studies to study age at onset according to previous recommendations [30]. Fifth, the definition of historic period at disorder onset was heterogeneous; we addressed this issue via sensitivity analyses. Sixth, we were not able to account for and differentiate amongst comorbid and standalone diagnoses. 6th, we were not able to account for differences beyond regions. Finally, caution is needed when comparing peaks (e.k., between symptoms and diagnosis), in particular when the height curves are unlike, and when comparison median age at onset across disorders (east-Tabular array v).

Conclusions

The meta-analytic, global, epidemiological evidence provided challenges the current mental health care organisation that artificially separates child/adolescent and adult mental health services, providing stiff epidemiologic evidence for the global implementation of integrated models of mental health promotion and preventive/early intervention care for immature people in the customs, those at risk for and with manifest mental disorders.

References

-

Hjorthøj C, Stürup AE, McGrath JJ, Nordentoft Yard. Years of potential life lost and life expectancy in schizophrenia: a systematic review and meta-assay. Lancet Psychiatry. 2017;4:295–301.

-

Walker ER, McGee RE, Druss BG. Mortality in mental disorders and global disease brunt implications a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015;72:334–41.

-

Saha Due south, Chant D, McGrath J. A systematic review of mortality in schizophrenia: Is the differential mortality gap worsening over time? Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2007;64:1123–31.

-

Nordentoft M, Wahlbeck K, Hällgren J, Westman J, Ösby U, Alinaghizadeh H, et al. Backlog mortality, causes of death and life expectancy in 270,770 patients with contempo onset of mental disorders in Denmark, Finland and Sweden. PLoS Ane. 2013;8:e55176.

-

Fusar-Poli P, McGorry PD, Kane JM. Improving outcomes of outset-episode psychosis: an overview. World Psychiatry. 2017;xvi:251–65.

-

Correll CU, Galling B, Pawar A, Krivko A, Bonetto C, Ruggeri One thousand, et al. Comparing of early intervention services vs handling as usual for early-phase psychosis: a systematic review, meta-analysis, and meta-regression. JAMA Psychiatry. 2018;75:555–65.

-

Fusar-Poli P, Bauer K, Borgwardt S, Bechdolf A, Correll CU, Practice KQ, et al. European college of neuropsychopharmacology network on the prevention of mental disorders and mental health promotion (ECNP PMD-MHP). Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.euroneuro.2019.09.006.

-

Fusar-Poli P, Correll C, Arango C, Berk Thou, Patel 5, Ioannidis J Preventive psychiatry: a blueprint for improving the mental health of young people. Earth Psychiatry. 2021;twenty:200–21.

-

Millan MJ, Andrieux A, Bartzokis G, Cadenhead K, Dazzan P, Fusar-Poli P, et al. Altering the course of schizophrenia: Progress and perspectives. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2016;15:485–515.

-

Fusar-Poli P. The clinical loftier-risk country for psychosis (CHR-P), version II. Schizophr Balderdash. 2017;43:44–7.

-

Fusar-Poli P, Salazar de Pablo G, Correll CU, Meyer-Lindenberg A, Millan MJ, Borgwardt S, et al. Prevention of Psychosis: Advances in Detection, Prognosis, and Intervention. JAMA Psychiatry. 2020;77:755–65.

-

Catalan A, Salazar de Pablo K, Vaquerizo Serrano J, Mosillo P, Baldwin H, Fernández-Rivas A, et al. Almanac inquiry review: prevention of psychosis in adolescents—systematic review and meta-assay of advances in detection, prognosis and intervention. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpp.13322.

-

Salazar de Pablo Thousand, Catalan A, Fusar-Poli P. Clinical validity of DSM-5 attenuated psychosis syndrome: advances in diagnosis, prognosis, and treatment. JAMA Psychiatry. 2020;77:311–20.

-

Salazar de Pablo G, Radua J, Pereira J, Bonoldi I, Arienti 5, Besana F, et al. Probability of transition to psychosis in individuals at clinical high adventure: an updated meta-analysis. JAMA Psychiatry. 2021. (In press).

-

Kotlicka-Antczak Thou, Podgórski M, Oliver D, Maric NP, Valmaggia L, Fusar-Poli P. Worldwide implementation of clinical services for the prevention of psychosis: the IEPA early intervention in mental health survey. Early on Interv Psychiatry. 2020:eip.12950.

-

Fusar-Poli P, Byrne G, Badger Southward, Valmaggia LR, McGuire PK. Outreach and back up in South London (OASIS), 2001–11: ten years of early diagnosis and treatment for young individuals at high clinical adventure for psychosis. Eur Psychiatry. 2013;28:315–26.

-

Salazar de Pablo 1000, Estradé A, Cutroni M, Andlauer O, Fusar-Poli P. Establishing a clinical service to prevent psychosis: what, how and when? Systematic review. Transl Psychiatry. 2021;11:43.

-

Fusar-Poli P, Spencer T, De Micheli A, Curzi V, Nandha S, McGuire P. Outreach and support in South-London (OASIS) 2001–xx: 20 years of early detection, prognosis and preventive care for young people at gamble of psychosis. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2020;39:111–22.

-

Fusar-Poli P, Davies C, Solmi M, Brondino Northward, De Micheli A, Kotlicka-Antczak Thousand, Shin JI, Radua J. Preventive Treatments for Psychosis: Umbrella Review (Just the Show). Front Psychiatry. 2019;10:764.

-

Davies C, Cipriani A, Ioannidis JPA, Radua J, Stahl D, Provenzani U, et al. Lack of bear witness to favor specific preventive interventions in psychosis: a network meta-analysis. World Psychiatry. 2018;17:196–209.

-

Bosnjak Kuharic D, Kekin I, Hew J, Rojnic Kuzman M, Puljak Fifty. Interventions for prodromal stage of psychosis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2019;11:CD012236.

-

Burke Equally, Shapero BG, Pelletier-Baldelli A, Deng WY, Nyer MB, Leathem Fifty, et al. Rationale, methods, feasibility, and preliminary outcomes of a transdiagnostic prevention program for at-chance college students. Front Psychiatry. 2020;10:1030.

-

Radua J, Ramella-Cravaro V, Ioannidis JPA, Reichenberg A, Phiphopthatsanee Due north, Amir T, et al. What causes psychosis? An umbrella review of adventure and protective factors. World Psychiatry. 2018;17:49–66.

-

Lindow JC, Hughes JL, South C, Minhajuddin A, Gutierrez L, Bannister E, et al. The youth enlightened of mental health intervention: impact on help seeking, mental health knowledge, and stigma in U.S. Adolescents. J Adolesc Health. 2020. https://doi.org/ten.1016/j.jadohealth.2020.01.006.

-

Salazar de Pablo Yard, De Micheli A, Nieman DH, Correll CU, Kessing LV, Pfennig A, et al. Universal and selective interventions to promote good mental wellness in immature people: systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol J Eur Coll Neuropsychopharmacol. 2020;41:28–39.

-

Fusar-Poli P, Salazar de Pablo M, De Micheli A, Nieman DH, Correll CU, Kessing LV, et al. What is good mental health? A scoping review. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2020;31:33–46.

-

Xu L, Guo Y, Cao Q, Li Ten, Mei T, Ma Z, et al. Predictors of outcome in early onset schizophrenia: a 10-twelvemonth follow-up report. BMC Psychiatry. 2020;twenty:67.

-

Chen 50, Selvendra A, Stewart A, Castle D. Risk factors in early and late onset schizophrenia. Compr Psychiatry. 2018;80:155–62.

-

Fagerlund B, Pantelis C, Jepsen JRM, Raghava JM, Rostrup E, et al. Differential effects of age at illness onset on exact memory functions in antipsychotic-naïve schizophrenia patients aged 12-43 years. Psychol Med. 2020:i–11.

-

Jones PB. Adult mental health disorders and their age at onset. Br J Psychiatry Suppl. 2013;54:s5–10.

-

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG; PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6:e1000097.

-

Stroup DF, Berlin JA, Morton SC, Olkin I, Williamson GD, Rennie D, et al. Meta-analysis of observational studies in epidemiology: a proposal for reporting. J Am Med Assoc. 2000;283:2008–12.

-

Wells GA, Shea B, O'Connell D, Peterson J, Welch 5, Losos Grand, Tugwell P. Newcastle-Ottawa scale appraise qual nonrandomised stud meta-analyses. Ottawa Hospital Research Institute. http://www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.asp. Accessed 21 Dec 2019.

-

Davison Air conditioning, Hinkley DV. Bootstrap methods and their application. Cambridge University Printing; 1997.

-

Zaboski BA, Merritt OA, Schrack AP, Gayle C, Gonzalez Chiliad, Guerrero LA, et al. Hoarding: A meta-analysis of historic period of onset. Depress Anxiety. 2019;36:552–64.

-

Immonen J, Jääskeläinen E, Korpela H, Miettunen J. Age at onset and the outcomes of schizophrenia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Early Interv. Psychiatry 2017;11:453–lx.

-

Eranti SV, MacCabe JH, Bundy H, Murray RM. Gender difference in age at onset of schizophrenia: a meta-analysis. Psychol Med. 2013;43:155–67.

-

Myles N, Newall H, Compton MT, Curtis J, Nielssen O, Large M. The historic period at onset of psychosis and tobacco use: a systematic meta-analysis. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2012;47:1243–fifty.

-

Fusar-Poli P, Solmi Yard, Brondino Northward, Davies C, Chae C, Politi P, et al. Transdiagnostic psychiatry: a systematic review. World Psychiatry. 2019;18:192–207.

-

Fusar-Poli P. TRANSD recommendations: improving transdiagnostic research in psychiatry. World Psychiatry. 2019;xviii:361–2.

-

Paus T, Keshavan K, Giedd JN. Why exercise many psychiatric disorders emerge during adolescence? Nat Rev Neurosci. 2008;9:947–57.

-

Gałecki P, Talarowska K. Neurodevelopmental theory of low. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2018;80:267–72.

-

Howes OD, Murray RM. Schizophrenia: an integrated sociodevelopmental-cognitive model. Lancet. 2014;383:1677–87.

-

Demjaha A, MacCabe JH, Murray RM. How genes and environmental factors decide the different neurodevelopmental trajectories of schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. Schizophr Bull. 2012;38:209–fourteen.

-

Gore FM, Bloem PJN, Patton GC, Ferguson J, Joseph V, Coffey C, et al. Global brunt of illness in young people aged x–24 years: a systematic analysis. Lancet. 2011;377:2093–102.

-

McGorry PD. Early intervention in psychosis: obvious, effective, overdue. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2015;203:310–8.

-

Bortolato B, Köhler CA, Evangelou E, León-Caballero J, Solmi Grand, Stubbs B, et al. Systematic cess of environmental risk factors for bipolar disorder: an umbrella review of systematic reviews and meta-analyses. Bipolar Disord. 2017;19:84–96.

-

Kim JY, Son MJ, Son CY, Radua J, Eisenhut Chiliad, Gressier F, et al. Environmental gamble factors and biomarkers for autism spectrum disorder: an umbrella review of the evidence. Lancet Psychiatry. 2019. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(19)30181-six.

-

Köhler CA, Evangelou E, Stubbs B, Solmi Yard, Veronese North, Belbasis L, et al. Mapping risk factors for depression across the lifespan: An umbrella review of evidence from meta-analyses and Mendelian randomization studies. J Psychiatr Res. 2018;103:189–207.

-

Tortella-Feliu M, Fullana MA, Pérez-Acuity A, Torres Ten, Chamorro J, Littarelli SA, et al. Risk factors for posttraumatic stress disorder: an umbrella review of systematic reviews and meta-analyses. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2019;107:154–65.

-

Fullana MA, Tortella-Feliu K, Fernández de la Cruz Fifty, Chamorro J, Pérez-Vigil A, Ioannidis JPA, et al. Hazard and protective factors for anxiety and obsessive-compulsive disorders: an umbrella review of systematic reviews and meta-analyses. Psychol Med. 2020;50:1300–1315.

-

Belbasis Fifty, Köhler CA, Stefanis North, Stubbs B, van Os J, Vieta Due east, et al. Risk factors and peripheral biomarkers for schizophrenia spectrum disorders: an umbrella review of meta-analyses. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2018;137:88–97.

-

Davies C, Segre G, Estradé A, Radua J, De Micheli A, Provenzani U, et al. Prenatal and perinatal risk and protective factors for psychosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Psychiatry. 2020;vii:399–410.

-

Arango C, Dragioti East, Solmi Thou, Cortese S, Domschke K, Murray R, et al. Evidence-based atlas of risk and protective factors of mental disorders: meta-umbrella review. World Psychiatry. 2021. (In press).

-

Werner-Seidler A, Perry Y, Calear AL, Newby JM, Christensen H. School-based depression and feet prevention programs for young people: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Psychol Rev. 2017;51:30–47.

-

Lai ES, Kwok CL, Wong PW, Fu KW, Police force YW, Yip PS. The Effectiveness and Sustainability of a Universal School-Based Program for Preventing Depression in Chinese Adolescents: A Follow-Upward Written report Using Quasi-Experimental Design. PLoS I. 2016;26;eleven:e0149854.

-

Strøm HK, Adolfsen F, Handegård BH, Natvig H, Eisemann Thousand, Martinussen One thousand, et al. Preventing booze use with a universal school-based intervention: results from an effectiveness study. BMC Public Health. 2015;xv:337.

-

Fusar-Poli P. Integrated mental health services for the developmental period (0 to 25 years): a critical review of the evidence. Front Psychiatry. 2019;10:355.

-

McGorry PD, Hartmann JA, Spooner R, Nelson B. Beyond the "at gamble mental land" concept: transitioning to transdiagnostic psychiatry. World Psychiatry. 2018;17:133–42.

-

Solmi G, Durbaba S, Ashworth Thou, Fusar-Poli P. Proportion of young people in the general population consulting general practitioners: potential for mental wellness screening and prevention. Early Interv Psychiatry. 2019. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1111/eip.12908.

-

McGorry PD, Hartmann JA, Spooner R, Nelson B. Beyond the "at risk mental land" concept: transitioning to transdiagnostic psychiatry. World Psychiatry. 2018;17:133–42.

-

Tuomainen H, Schulze U, Warwick J, Paul Thousand, Dieleman GC, Franić T, et al. Managing the link and strengthening transition from child to developed mental health Care in Europe (MILESTONE): background, rationale and methodology. BMC Psychiatry. 2018;18:167. https://doi.org/ten.1186/s12888-018-1758-z. Erratum in: BMC Psychiatry. 2018;18:295.

-

Russet F, Humbertclaude 5, Dieleman G, Dodig-Ćurković Thou, Hendrickx G, Kovač V, et al. Training of adult psychiatrists and child and adolescent psychiatrists in Europe: a systematic review of preparation characteristics and transition from child/boyish to adult mental health services. BMC Med Educ. 2019;nineteen:204.

-

Leavey K, McGrellis S, Forbes T, Thampi A, Davidson G, Rosato 1000, et al. Improving mental health pathways and care for adolescents in transition to adult services (Bear on): a retrospective case notation review of social and clinical determinants of transition. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2019;54:955–63.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by Wellcome Trust Innovator Grant to PFP. Furthermore, the study was supported past Miguel Servet Inquiry Contract (CPII19/00009 to JR), Alicia Koplowitz Foundation and Research Project Grants (PI19/00394) from the Instituto de Salud Carlos Three and co-funded by European Wedlock (ERDF/ESF, 'Investing in your future'). JBK is supported by the National Plant of Health Research University College London Infirmary Biomedical Inquiry Centre.

Writer information

Affiliations

Contributions

PFP conceived the study, which was led past MS and JR. MO, EC, LS, GSdP extracted the information nether the supervision of MS. MS, JR and PFP drafted the piece of work, and JR conducted the analyses. JIS, JBK, PJ, CUC made substantial contributions to the interpretation of the results. All authors revised the manuscript critically for important intellectual content, canonical the concluding version for publication and agreed to exist accountable for all the aspects of the work. MS, JR had total admission to all the data in the report and can have responsibility for the integrity of the information and the accurateness of the information analysis.

Corresponding author

Ideals declarations

Conflict of interest

MS has been a consultant and/or counselor to or has received honoraria from Angelini, Lundbeck. CUC has been a consultant and/or advisor to or has received honoraria from Acadia, Alkermes, Allergan, Angelini, Axsome, Gedeon Richter, Gerson Lehrman Grouping, IntraCellular Therapies, Janssen/J&J, LB Pharma, Lundbeck, MedAvante-ProPhase, Medscape, Neurocrine, Noven, Otsuka, Pfizer, Recordati, Rovi, Sumitomo Dainippon, Sunovion, Supernus, Takeda, and Teva. He has provided expert testimony for Janssen and Otsuka. He served on a Information Safety Monitoring Lath for Lundbeck, Rovi, Supernus, and Teva. He received royalties from UpToDate and grant support from Janssen and Takeda. He is also a stock option holder of LB Pharma. PF-P has received grant fees from Lundbeck and honoraria from Lundbeck, Menarini and Angelini, outside the electric current piece of work. All other authors declare no conflict of interest.

Boosted information

Publisher'south note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits apply, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in whatsoever medium or format, equally long as yous give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other 3rd party cloth in this article are included in the article's Creative Eatables license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the commodity's Creative Commons license and your intended employ is non permitted past statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted employ, you lot will demand to obtain permission straight from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

Reprints and Permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Solmi, Thousand., Radua, J., Olivola, M. et al. Historic period at onset of mental disorders worldwide: large-scale meta-analysis of 192 epidemiological studies. Mol Psychiatry 27, 281–295 (2022). https://doi.org/ten.1038/s41380-021-01161-7

-

Received:

-

Revised:

-

Accepted:

-

Published:

-

Outcome Date:

-

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1038/s41380-021-01161-seven

Farther reading

Source: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41380-021-01161-7

Post a Comment for "Age of Onset of Mental Disorders a Review of Recent Literature"